North America’s first Europeans: evidence of Vikings in Newfoundland

Our Transatlantic cruise aboard Holland America’s Amsterdam was nearing its end, and we were continuing southwest, in the pathways of the Vikings, to Newfoundland. Together with Labrador it became Canada’s 10th and newest province in 1949.

St. Anthony, Newfoundland

Our port was St. Anthony, population about 3000, a remote well-protected harbor on the North Peninsula. Teeming with wildlife, the area was centered for centuries on a flourishing fishing industry.

When John Cabot explored the area in 1497, he reported a “Land of Cod” where fish were so plentiful that they slowed his ships. The Grand Banks, featured in Kipling’s Captain’s Courageous, and the movie Perfect Storm, benefits from a cold Labrador Current, warm Gulf Stream, and relatively shallow waters. This was one of the world’s richest fishing and spawning grounds. Several decades ago, annual yields of cod were in the hundreds of thousands of tons.

With the advent of large factory trawlers, both foreign and Canadian fleets caught increasingly larger numbers of fish. The ocean bottom was trawled with huge weighted nets that picked up everything in their path, destroying the cod habitat and disrupting the breeding grounds. The Canadian government banned foreign fishing, but its own trawling was expanded with economic incentives. In the 1990s, what was then called a temporary cod moratorium was imposed, closing major fisheries and abruptly putting tens of thousands of fishermen out of work. Compensation packages and retraining gave some immediate relief, but the moratorium continues today, with profound economic and social fallout in an area like this where for generations and from an early age lives have been built around the sea.

The purpose of this world is not to have and hold, but to serve. – Wilfred Thomason Grenfell

Take some time to explore this area. Dr. Wilfred Thomason Grenfell was inspired to a life of charity by an American evangelist. He came to Newfoundland in 1892 from England to investigate conditions, and finding no medical services, he remained here. He practiced medicine and went on to create cottage hospitals, schools, and orphanages. The home he shared with his wife and three children overlooks the hospital and is now a museum. Lining the rotunda of the Charles S. Curtis Hospital are dramatic ceramic murals depicting the people of Newfoundland and Labrador.

The Grenfell Interpretation Center offers self-guided tours and a short video on his life and work. Dr. Grenfell was impressed by the local handicrafts and encouraged a cottage industry. The shop at the Grenfell Center offers locally made hand hooked rugs and hand embroidery.

This is the sort of place where tourists receive a warm welcome. In the unlikely event the local motels are full, our guide told us to “just knock on someone’s door and they’ll find a place to put you up.” Local bars hold screech-ins, a rum-laden ceremony of initiation as an honorary Newfoundlander.

This is the northern corridor of Iceberg Alley, with more icebergs than in any other part of Newfoundland. Most of the icebergs, growlers, and bergy bits sighted have drifted from Greenland’s glaciers. Boat tours sail past these frozen time capsules, some of which may be over 10,000 years old, and offer sightings of whales spouting and seabirds gliding by. The twenty minute walking trail on Tea House Hill offers an overview of the area. Or simply relax at Lady Anne’s Tea Room with some local specialties, including moose soup and local iceberg water. One nearby site, however, should not be missed.

L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site

St. Anthony is the gateway to L’Anse Aux Meadows, the first and only authenticated Norse settlement in North America. It was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in recognition of its significance in the history of worldwide exploration and the movement of peoples. In 2000, it attracted attention and large crowds when the landing of the Vikings 1000 years earlier was celebrated.

Our guide, Andrew Colbourne, lived in Griquet’s Dark Tickle area, named for the narrow channel (tickle) surrounded by hills that cast shadows on the water. A volunteer firefighter, he hoped to remain in this area. With limited local employment opportunities, he recently signed a five year military contract.

Area people were needed to serve as guides to accommodate the cruise passengers, and we were led us on an unscripted journey that only a local could tell. We learned about the ghost stories at the Parish Hall, duck hunting, the deep swimming hole at Triple Falls, and furnished homes selling for the price of a typical new family sedan.

The flag hung at half-staff for a Canadian soldier killed in Afghanistan. Retirement homes, the hospital, and a Salvation Army store dominate the center of town. We traveled past unspoiled landscapes and scenic fishing communities, noting the absence of the usual tourist trappings and entertainment. Here there is a clear appreciation and use of what the land has to offer.

Moose is the local beef. Caribou, muskrat, beaver, and duck are abundant. In summer young folks make money picking berries for The Dark Tickle Company’s jam.

We continued along Highway 430, the Viking Trail, passing small motels and restaurants, most with Viking names and themes, like Snorri Cabins, named for the first known Viking baby born at L’Anse aux Meadows. At the tip of western Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula, Anglicized from the original name, l’Anse aux Meaduses, “jellyfish bay”, is the earliest evidence of European settlers in the Western Hemisphere.

The Visitor Center and museum is run by Parks Canada. The historic area remains much as it was when the Vikings, the first European settlers, arrived 500 years before Columbus. At L’Anse aux Meadows, Norse-style huts of sod have been built over a timber frame, using local materials available to Norse colonists over 1000 years ago. Costumed interpreters recreate Viking life in these dark, smoky longhouses where Vikings lived, ate and worked.

History

Around 1000 AD, Leif Eriksson, son of Erik the Red, was accused of murder and banished from Greenland. He sailed westward with thirty others and arrived at this sheltered harbor. Crewmember Tyrkir, the German, is said to have found grape vines in the forest. They brought wood and wine back to Greenland, and the name Vinland, “Land of Wine” developed. Soon 135 settlers returned to this strategic area, a base camp from which they would explore south into the Gulf of St. Lawrence. They were welcomed at first by the native people, probably Mi’kmaqs, whom they referred to as Skraelings, or barbarians. Their experiences were later recorded in the ancient Viking Sagas, Norse tales compiled in the Middle Ages from centuries of oral history.

Over next decades, the Norsemen made a number of voyages to the site, mainly in search of hardwood lumber. There was a major conflict with the Skrealings, ending the settlement.

Danish archaeologists had been excavating Greenland since 1930s. Locals had long known about this site, thought to be remains from First Nations, as the indigenous people are known in Canada. The First Nations, however, had told of finding a strange house in this area long ago…

In 1960, Norwegian explorer and writer Helge Ingstad and his archaeologist wife Anna Steine Ingstad were following The Saga of Eric the Red and The Saga of the Greenlanders. They knew the Norsemen were traders looking for good land to settle on. Landless people, second or third sons would have made up much of the crew. The sagas mention a fjord of currents, Straunfjord, and a summer camp Hop. Both were also referred to as Leifsbudir (Leif’s camp). The Ingstads sought proof that the Vikings landed in North America. A local resident led them here.

Loretta Decker, granddaughter of George Decker, the local fisherman who led the Ingstads to one of the world’s most significant archaeological discoveries, was our guide and recreated the experience for us.

Only a few ridges were apparent at first, but as the sun set one night the Ingstads recognized a line of foundations in the pattern of Norse longhouses. They returned with a team of archaeologists and mysteries began to unravel. The Norsemen had left behind evidence of their presence that would prove that the first contact between Europeans and North Americans was here.

Remains of 8 -11th century Norse buildings emerged that were similar to Icelandic structures of that time. There were foundations of three large houses, indicating three ships and around seventy-five people, including sailors, carpenters, and blacksmiths. A building with a conical roof was for hired hands or, perhaps, serfs or slaves.

Charcoal and evidence of a smithy revealed the use of local bog ore to produce iron, a technology otherwise unknown at that time in North America. The discovery of broken rivets and nails showed that the Norse made basic items needed to repair their ships.

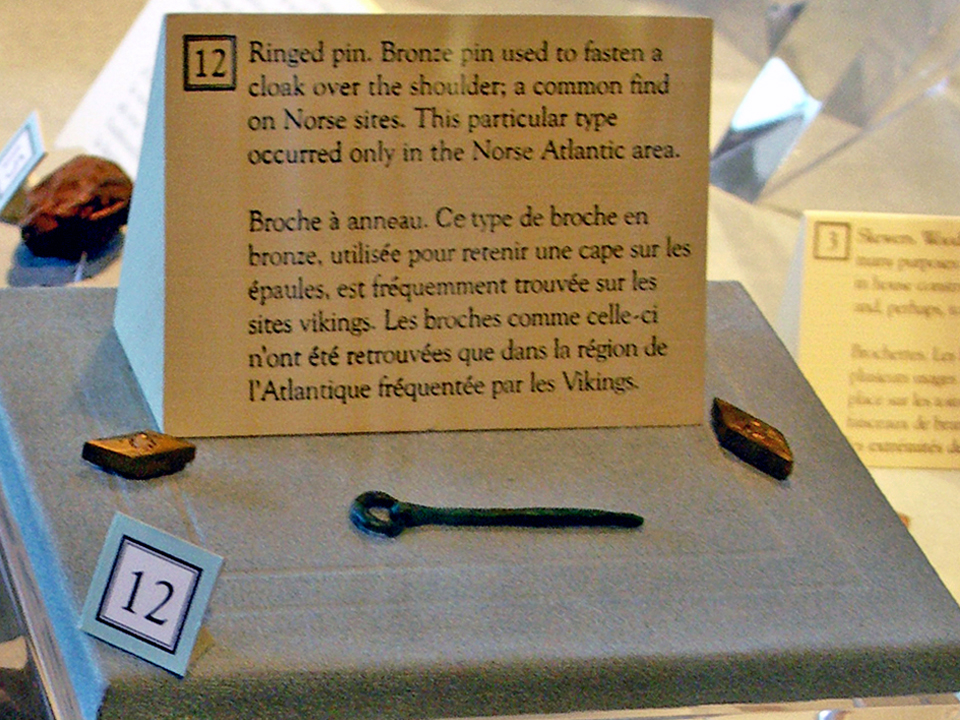

The L’Anse aux Meadows Visitor Center exhibits a bronze ring-headed cloak pin that was found– clear proof of the Norse Norse presence in the North Atlantic over 1000 years ago. A small spindle whorl, part of a thread spinning kit, a fragment of a bone needle, and a small whetstone for sharpening it revealed the presence of Norse women. .

The Nordic artifacts are unmistakable evidence that the Vikings were here. Was this Straunfjord? Foremost authority Senior Archaeologist Emeritus of Parks Canada, Birgitta Wallace, who worked with the Ingstads as a student and continued the later digs, is convinced that it is.

Everything seemed to fit the Sagas except the grapes. Wild grapes are found today only as far north as Southern New England. Was the climate warmer at that time, enabling grapes to grow? The Sagas say the Norsemen drank a sweet tasting dew from the ground. Does the Norse word for grapes refer to all berries, like red currants, which can be made into wine?

Shells and husks of butternuts, used to make dark brown dye, and not native to this region, were found. There is no indication that the native people brought butternuts here. It appears that there were explorations as least as far as the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where butternuts –and grapes—are found.

There was evidence of fishing, buildings, and iron smelting, but not animals, usually a part of a permanent settlement. Was it used primarily in winter when the seas were frozen and otherwise as a base for hunting, fishing, and summer explorations?

The Norsemen left after a few years, and no one knows for sure where they went. Both the Sagas and First Nations told of a fierce battle with much bloodshed around the time the settlement ended. Had most died in the conflict? No grave sites were found, but he Norse had recently converted to Christianity and usually brought remains back to churchyards. Had they simply gone home?

Norstad

Adjacent to L’Anse Aux Meadows in the Norstad Viking Trade Village, staffed by costumed reenactors. Visit and you might be asked whether you have any dyes to trade– woad for blue, yarrow for mint green, weld for yellow, madder root for red. Viking wives may have shell brooches or Venetian beads. Were they plundered or traded? This isn’t a question to ask.

Watch as pig fat is first boiled for soup then burned for use in caulking ships. Buy jewelry hand-carved from shed reindeer antlers. It’s a unique and entertaining finish to a remarkable day.

© 2014 : All Rights Reserved. No part of this site may be reproduced, copied, or borrowed without contacting us for written permission. Contact information is available under the About Notable Travels tab at the top of the page.